Healing after hate

I am co-teaching a new study abroad course at the University of Georgia that looks into Rwanda's reconciliation and reconstruction after the 1994 genocide. There are critical lessons to be learned.

I have been visiting journalism classes at the University of Georgia to promote a new study-away program next May. It’s not in any of the popular destinations for college students at predominantly white universities — not in England, France, Spain, Italy, or Greece. Not anywhere in Europe. Or in Australia or Canada. This course is in Rwanda.

The topic, for sure, is heavy: reconstruction and reconciliation after genocide. I have been explaining to students how that word has so much controversy swirling around it these days. Global leaders cannot seem to agree on whether the extermination of nearly 70,000 Palestinians constitutes genocide.

The United Nations defines genocide as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such:

A: Killing members of the group;

B: Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

C: Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

D: Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

E: Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

So, genocide, according to the world body, is not just mass killing but “the deliberate aim to destroy a group as such.” In other words, genocide is not just about the act itself but about the intent of the perpetrators.

A genocide occurred in the spring of 1994 when Hutus turned against Tutsis in Rwanda. The Rwandan genocide lasted only 100 days, but between April and July of that year, 800,000 ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutu were butchered. Sadly — unconscionably — the world stood by and did nothing to stop the killings.

Part of the UGA study-away course will look at the brutal history of colonial control in Africa to understand why the Rwandan genocide occurred. First the Germans and then the Belgians exploited ethnic divisions for their own gain. Divide and rule was a method used most effectively by the British in my own country, India.

In Rwanda, the majority Hutus were left in control after the country finally gained independence in 1962. But by then, ethnic animosity was deeply rooted, and Hutu rule resulted in widespread discrimination against the minority Tutsis. In the years leading up to the genocide, Tutsi insurgents had waged a civil war, and when the Hutu president’s plane was shot down in 1994, all hell broke loose. Neighbors, family members — no one was spared. Desperate Tutsis sought refuge in schools and churches, hoping to be protected by United Nations peacekeepers, but they did not act.

I just started reading Samantha Power’s book A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. It was published in 2002, when Power was a professor of Human Rights Practice at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government — a time when several nations — among them Iraq, Cambodia, Bosnia, and of course Rwanda — were reckoning with ethnic cleansing within their borders. The world had said “never again” after the Holocaust, and yet, in the years since, America stood by and did little to end the carnage. That, I believe, was also true in the two years of the war in Gaza.

“The United States did virtually nothing to try to stop it,” writes Power about the Rwandan genocide. The Clinton administration did not even use the word genocide in public, Power writes, because that would “trigger calls for intervention that they were unwilling to comply with.” Perhaps the same can be said about Gaza — and why, even now, after all this killing, after human rights groups have declared it to be so, U.S. officials steer clear of that term.

“I don’t think it’s that. They’re in a war,” Donald Trump said back in August.

The point of the UGA course in Rwanda is not solely to look back at what led to the genocide but to examine how the country moved forward after the tragedy. How do you go on after carnage? After so much hatred and misinformation? After all trust is broken? These are questions that could easily apply to the United States today. We have not suffered genocide, but sometimes I think that the idea of one happening is not entirely outrageous. The Trump administration has sown the seeds of hate against so many people — Black people, Brown people, LGBTQ people, women, social democrats. Hell, all Democrats. Journalists. And, yes, even professors.

What we are witnessing these days in America ought to be frightening. I think about the incident in Chicago several days ago, when Black Hawks hovered over an apartment building in the South Shore neighborhood in the middle of the night as masked ICE agents rappelled from the choppers, broke down doors, zip-tied people, and whisked them away. Some were U.S. citizens. That’s just one of many incidents that seem in line with what has happened in countries that have allowed genocide. Human beings tolerate inhuman actions only when they believe the victims are not as human as they are. The Germans convinced their citizens that the Jews were subhuman vermin. The Hutus convinced their people that the Tutsis were cockroaches.

I look at Rwanda today and wonder what it feels like to live in a society that endured such atrocities. I have been interested in recovery and resilience for a while now. Much of my journalism has centered on going back to people who suffered loss to see how they fared in the days, months, and even years after. That’s why I volunteered to co-teach this UGA class. What a tremendous opportunity to speak with genocide survivors — and perpetrators — about how they live side by side today. I want to know how they have healed the holes in their hearts. Or not. What does it mean to be Rwandan now?

Last year, I tried to launch a study-away program in Cape Town, South Africa. I had hoped UGA students would be able to learn how that country went from a horrific system of apartheid one day to rightful Black majority rule the next. I thought there were important lessons there for our students to consider when thinking about our own nation’s legacy of slavery. I could not get the 20 students we needed to sign up for that program. I was disappointed, to say the least. It’s imperative, I think, for students from a predominantly white college to have the desire to travel to countries of color that are so different from our own and yet have important lessons to teach us about our institutional flaws.

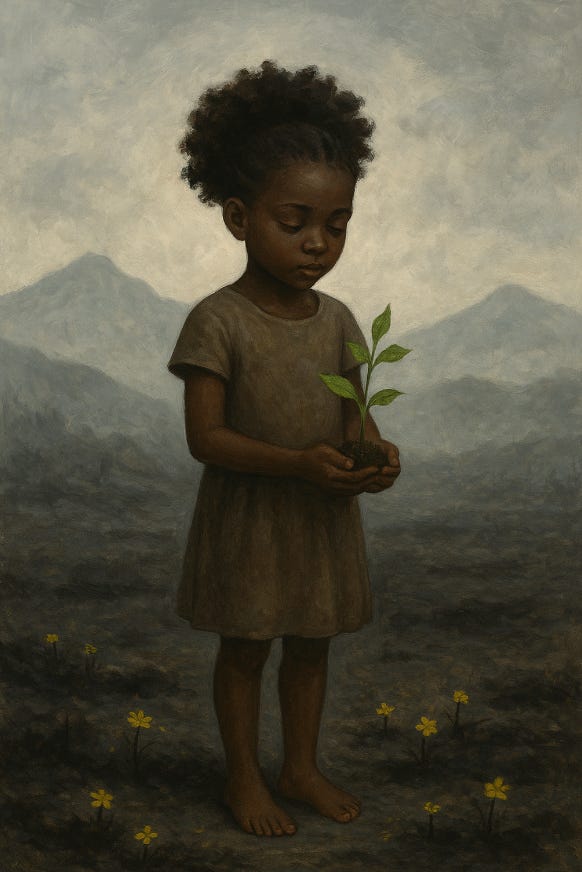

I am keeping my fingers crossed that the Rwanda program is strong enough to attract the minimum number of students we need. We’ve planned a safari on the itinerary. Perhaps that will be enough for UGA students to want to know more about why people kill one another — and how, to borrow a phrase from my former MFA student and CNN colleague Samantha Bresnahan’s book, even in rivers of blood, flowers can bloom.

Courses like this should be a requirement.

Unfortunately “study abroad” often insinuates a pleasure trip for students in romantic settings. This is a more challenging sell, but I do hope that students choose to be educated about genocide and a country’s recovery. Our future leaders need that knowledge, now more than ever. Bravo, Monimala, for co-leading this course.